Blooming in Jade: Plant Motifs on Longquan Celadon

Exploring the Symbolism and Beauty of Nature in China’s Famous Green-Glazed Ceramics

Longquan celadon—the luminous, jade-like ceramics fired in Zhejiang province—captures the imagination with its cool, translucent glaze. Yet, beyond this surface beauty lies a sophisticated symbolic language of plants rendered in clay. Orchids, lotus flowers, grapevines, scrolling leaves, and even vegetal forms inspired by everyday flora are far more than mere decoration. They are visual metaphors rooted deeply in Chinese culture, each carrying layers of meaning regarding virtue, harmony, prosperity, and spiritual aspiration.

Why Plant Motifs Matter in Longquan Celadon

Longquan celadon, particularly at its height during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), reflects a cultural preference for restraint, subtlety, and natural harmony. Its jade-like glaze linked it both aesthetically and philosophically to nephrite jade, a material associated in Chinese thought with purity, integrity, and moral refinement.

Botanical decoration complemented this aesthetic perfectly. Eschewing bright colors or busy pictorial scenes, artisans rendered plant motifs through soft incisions, low relief, and rhythmic repetition. These designs connected the ceramics to the broader worlds of poetry, painting, and philosophy, where plants functioned as essential ethical and symbolic metaphors.

Meiping Form: Plum Blossoms, Restraint, and Enduring Elegance

The meiping (梅瓶), literally meaning “plum vase,” is one of the most iconic ceramic forms in Chinese art. Originally designed to hold a single branch of plum blossoms, the meiping is characterized by a small mouth, broad shoulders, and a gently tapering body. Its elegant proportions reflect an ideal of balance, aligning closely with the minimalist aesthetics of the Song dynasty.

The association between the meiping form and the plum blossom (梅, méi) is both functional and symbolic. In Chinese culture, the plum blossom blooms in the depths of winter and is celebrated as a symbol of resilience, renewal, and moral integrity. Because it flowers before other plants awaken, it signifies hope and perseverance in the face of hardship—qualities admired by scholars and officials alike.

On Longquan celadon, the meiping often conveys plum symbolism through shape rather than surface decoration. The vessel’s strong shoulders evoke the sturdy trunk of a plum tree, while its tapering lower body suggests controlled growth and inner strength. Even without carved blossoms, the form alone communicates the virtues of the plum. Notable variants include the Meiren Zui (美人醉) and the yuhuchunping (玉壶春瓶).

Gourd Motifs: Prosperity, Health, and Protection

In Chinese culture, the gourd (葫芦, hulu) has long been regarded as a premier symbol of good fortune and protection. Its linguistic significance is rooted in its name, which serves as a homophone for fú lù (福禄), or “fortune and emolument,” representing both spiritual prosperity and material success. Beyond its name, the gourd’s unique, double-lobed shape is steeped in Daoist mythology; it was traditionally viewed as a "container of the cosmos" or a vessel for life-extending elixirs held by the immortals. This association gave the gourd the perceived power to absorb negative energy and ward off evil spirits, making it a powerful auspicious symbol for the home.

On Longquan celadon, the gourd motif often transcends surface decoration to define the physical architecture of the vessel. Rather than simply painting a gourd onto a flat surface, Longquan artisans sculpted the clay into the fruit’s natural, organic silhouette. Pieces such as the Gourd-Shaped Miniature Vase turn the entire object into a three-dimensional talisman of longevity and protection. The soft, rounded curves of the double-lobed form are particularly well-suited to the thick, unctuous celadon glaze, which pools in the "waist" of the gourd to highlight its sculptural depth. By merging this ancient shape with the jade-like glaze, the artisans created a functional object that doubled as a silent prayer for a safe and prosperous life.

Orchids, Grapes, and Floral Scrolls

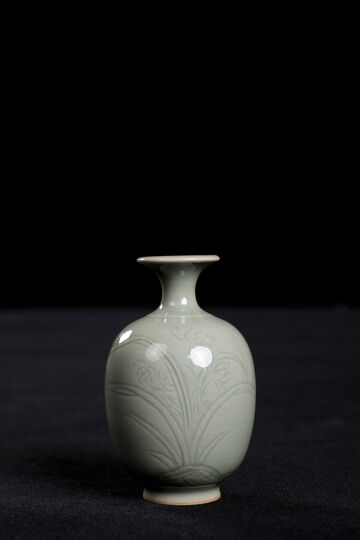

Orchids (兰, lán): In the Chinese literati tradition, the orchid is known as the "flower of ethical refinement." Because it thrives in secluded valleys, releasing its fragrance even when no one is there to appreciate it, it became the ultimate symbol of the humble scholar’s inner strength and integrity. On the Orchid Miniature Vase, this "quiet virtue" is captured through a technique of masterfully light incision. The slender, blade-like leaves are carved so delicately that they remain nearly invisible under a thick celadon glaze, only revealing their elegant curves as light shifts across the vessel’s surface—a visual metaphor for a virtue that does not seek the spotlight.

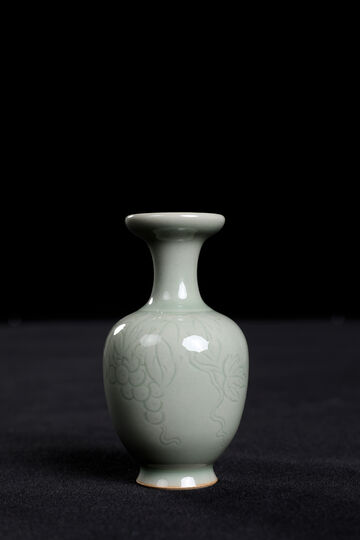

Grapes and Vines: Originally introduced to China via the Silk Road, the grapevine was quickly adopted as a potent symbol of abundance and continuity. Because grapes grow in heavy, clustered bunches, they represent the wish for "many sons and grandsons" (duo zi duo sun), while the evergreen, twisting nature of the vines implies a long, unbroken family lineage. In Longquan ceramics, these motifs are often rendered in high relief or deep carving. The thick, "plum-green" glaze pools around the grape clusters, creating a sense of juicy, three-dimensional vitality that suggests a life overflowing with success.

Floral Scrolls: Moving beyond specific species, many Longquan wares utilize stylized floral scrolls to emphasize movement, rhythm, and cosmic balance. These patterns represent the "continuous breath" of nature. The Eight-Sided Ewer with Incised Flowers and the Carved Floral Gu Vase demonstrate how rhythmic leaf motifs—often based on the acanthus or peony—can enrich a vessel’s surface without overwhelming its form. By repeating these undulating lines, artisans achieved a sense of "dynamic stillness," where the decoration flows around the vessel’s geometry to create a harmonious, unified whole that feels alive yet perfectly restrained.

Lotus, Chrysanthemum, and Vegetal Forms

The lotus (莲, lián) is perhaps the most spiritually resonant plant in the Longquan repertoire, representing purity and spiritual awakening. Because it rises unsullied from muddy waters, it became a primary Buddhist symbol for the soul’s triumph over worldly attachment. In Longquan ware, this is often expressed through "lotus-petal" motifs—radiating, relief-carved petals that wrap around the exterior of wash basins or tea bowls, making the vessel appear as if it is a flower in mid-bloom. Sculptural lids for storage jars also frequently mimic the broad, protective canopy of a lotus leaf, merging functional coverage with a sense of organic serenity.

Similarly, the chrysanthemum (菊, jú) serves as an emblem of purity and resilient integrity. As one of the "Four Gentlemen" of Chinese art, it is celebrated for blooming in the late autumn chill when other flowers have withered, symbolizing the ability to remain steadfast under pressure. On Longquan ceramics, such as the Plate with Chrysanthemum Petal Design, artisans used the plant’s naturally layered, linear petals to create rhythmic, fluted rims that catch the thick celadon glaze, creating alternating highlights and deep pools of green.

Even humble vegetables are elevated through the Chinese tradition of visual puns. The cabbage (Baicai) is frequently depicted because its name is a homophone for "hundred wealth" (百财, bǎicái). By sculpting the ruffled, organic edges of cabbage leaves into vases or jars, artisans created "auspicious objects" believed to attract prosperity and abundance to a household. These vegetal forms demonstrate how Longquan celadon bridged the gap between high-minded scholarly ideals and the practical, folk-driven desire for a fortunate life.

A Broader Botanical Palette

In addition to those mentioned above, Longquan celadon features a variety of other plant motifs, including bamboo, banana leaves, pine, peony, and water plants, each carrying its own symbolic meaning. Bamboo and pine, often paired with the plum as the "Three Friends of Winter," signify steadfastness and longevity. The peony represents wealth and honor, while banana leaves and various water plants evoke the scholars' appreciation for the lush, rhythmic beauty of the natural landscape.

Why These Motifs Still Matter

Plant motifs evolved alongside Longquan celadon itself. Song dynasty wares emphasized subtle incised decoration and poetic understatement; Yuan dynasty pieces introduced deeper carving and more dynamic motifs such as grapevines; Ming dynasty works featured denser ornamentation and increased visual richness.

Plant motifs on Longquan celadon remind us that these ceramics were never merely utilitarian. They were carriers of meaning, translating ideas about morality, prosperity, and spirituality into enduring material form. Through orchids, grapes, lotus petals, and scrolling leaves, Longquan celadon continues to speak across centuries—quietly, poetically, and profoundly.